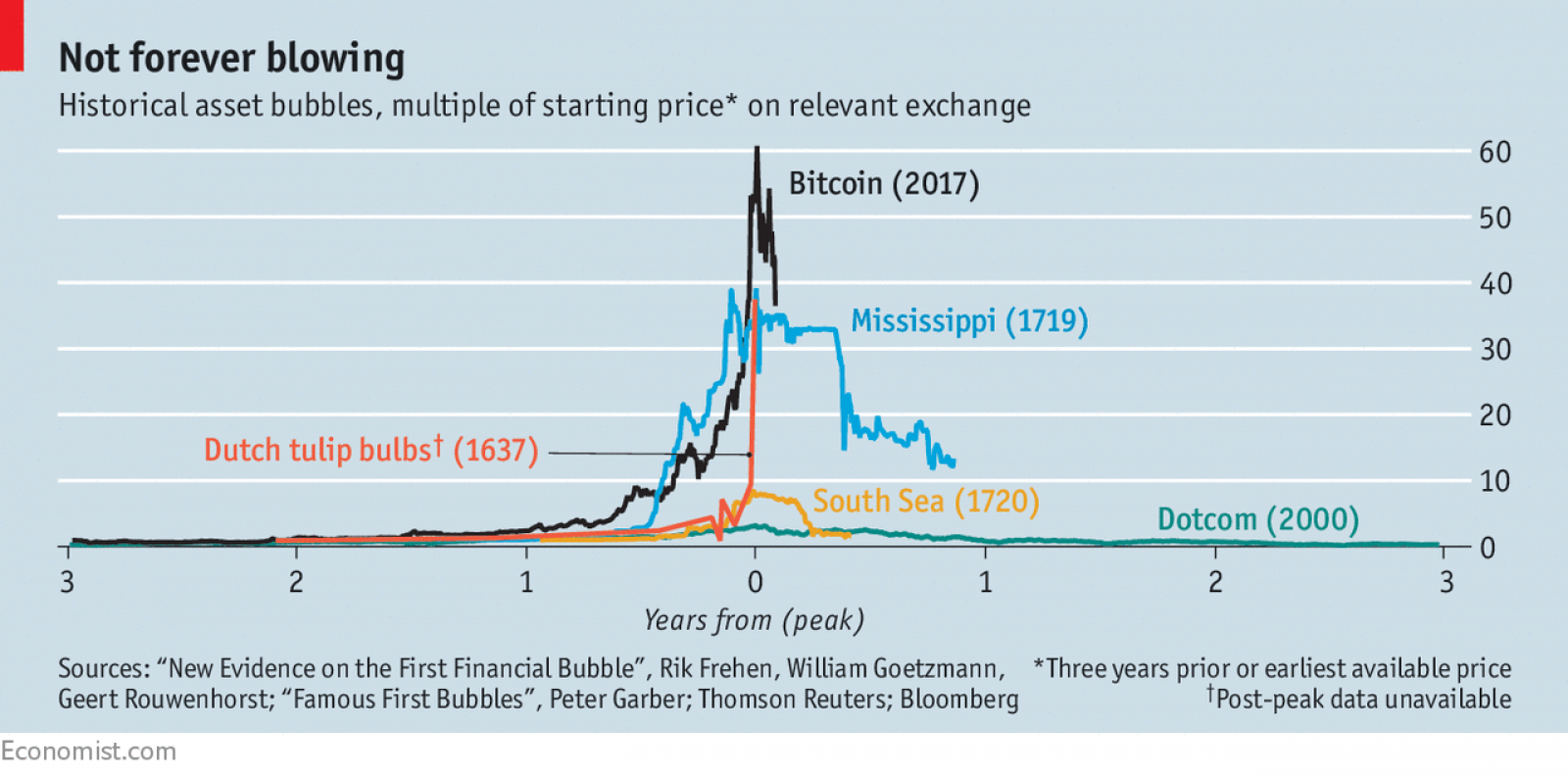

IT HAS been another week of vertiginous swings in the prices of bitcoin and other crypto-currencies. This time, the moves have mostly been downwards, with some days seeing falls of over 20%. Views on this were as divided as they were during the giddy climb: did it mark the definitive bursting of a bubble as rapidly inflated as any in history (see chart)?

Asia provides both an explanation of this week’s sell-off and a glimpse of crypto-currencies’ future. The threat of a ban in bitcoin-trading in South Korea was the proximate cause of the plunge. As to the future, the question is which Asia? At one end of the spectrum is Japan, which has embraced crypto-currencies. At the other is China, which has all but banished them. South Korea has been in the middle.

These countries have outsized roles in the crypto universe. China’s exchanges hosted more than nine-tenths of global bitcoin-trading until the government closed them last year. Japan now has the biggest share of virtual-currency markets. South Korea makes up less than 2% of global GDP but nearly a tenth of bitcoin-trading.

North Asia has been fertile ground for crypto-currencies for several reasons. Partly it is the high-tech pedigree. A prevalence of smartphones, fast internet and computer-science graduates makes people receptive to the newfangled. The rigidity of conventional finance has helped. Capital controls boost the appeal of crypto-currencies in China and South Korea, and in Japan they are a beguiling alternative to low-yielding mainstream investments. A zest for gambling has surely lured some to a market that is driven by speculation.

But the region’s regulators are going in different directions. China, alarmed at the way crypto-currencies can evade government oversight, has taken the harshest line. Last year it banned domestic exchanges; in recent days it has taken aim at websites flouting this ban. Officials have also called on local authorities to choke off the power supply to bitcoin miners, computer networks that create new coins through massively energy-intensive calculations. China’s miners, still dominant in the global industry, are shifting to other countries.

The Chinese government admires the technology that underpins virtual currencies and wants to reap the benefits. It is prodding its big financial firms to experiment with blockchain, a system of distributed ledgers popularised by bitcoin. But officials believe they can do this without having to tolerate the currencies themselves. As Pan Gongsheng, deputy governor of the central bank, quipped last year, quoting a French economist: “The only thing to do is to sit by the riverbank and wait for bitcoin’s corpse to float past.”

Japan, by contrast, has given crypto-currencies room to run. Its regulators know the dangers. One of the biggest scandals in bitcoin’s short history was the collapse of Mt. Gox, a Japan-based exchange, in 2014. And officials have not minced their words, with Haruhiko Kuroda, governor of the Bank of Japan, warning that the bitcoin rally in late 2017 was “abnormal”.

But rather than throttle virtual currencies and the innovations they might spawn, the government has let them develop, within parameters. Last March it passed the “virtual-currency act”, declaring that they are assets and can be used for payments. The financial-services authority has granted licences to 11 exchanges, to reduce the risk of fraud. Zennon Kapron, a Shanghai-based analyst of digital currencies, says that some of China’s leading crypto-coders are now moving to Japan.

South Korea was initially hands-off in its regulations. But alarm has mounted about the speculative fervour. So intense is the demand that South Koreans pay a “kimchi premium” of roughly 40% for their bitcoins (not easily arbitraged away because of capital controls). On January 11th the justice minister said crypto-currency exchanges would be banned. Their devotees responded with a petition urging leniency, which swiftly collected more than 200,000 signatures.

Faced with this backlash, the government appeared to soften its stance, saying a ban was just one idea. Other incoming measures are less potent: investors will have to pay taxes on capital gains and register trading accounts under their real names. But just as crypto-markets had recovered their poise, South Korea’s finance minister said this week that the ban was still very much on the table, calling it a “live option”. The collapse resumed.

Virtual currencies have bounced back from past sell-offs, but this has been a big one. At one point bitcoin was down about 50% from its highs in December. Believers in virtual currencies say that one of their selling points is freedom from government meddling. In Asia, the cutting edge of the crypto-world, it is governments that are making—and breaking—their fortunes.

Original article and pictures take cdn.static-economist.com site